Title: Otōto no Otto (My Brother’s Husband / 弟の夫 )

Title: Otōto no Otto (My Brother’s Husband / 弟の夫 )

Author: Gengoroh Tagame (Story & Art); English Translation: Anne Ishii

Genres: Drama, LBGTQ, Comedy, Slice of Life, Seinen

Rating: All

Published: 2015 – 2017 (tankōbon)

Volumes: 4 [Complete]

Japanese Publisher: Futabasha

English Publisher: Pantheon Books

Available to Purchase in English?: Yes (Indigo / Amazon / Barnes & Noble [omnibus edition] )

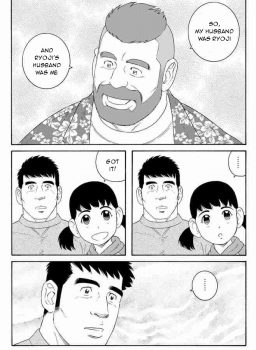

Synopsis: ‘Otouto no Otto’ is a family drama that begins with the suspicious arrival of Mike, a Canadian who has come to pay respects to the family of his recently deceased Japanese husband Ryouji, whose only remaining immediate family member is Yaichi—his identical twin brother. As Mike gets accustomed to Japanese morals and the surprising idiosyncrasies of living with Yaichi and his daughter Kana, the sleepy Japanese suburb also learns the true meaning of family. (MAL)

A few months ago I came across this title at my bookstore job and knew instantly that I wanted to read it. People familiar with Japanese culture are sometimes aware that Japan is different from other first-world countries on social topics like women’s rights, gay marriage and LGBTQ rights. I wanted to know how this manga tackled those issues. Plus Mike is Canadian and I’m Canadian, so you know, I gotta see how my country is represented. 😉

First a little background on LGBTQ rights in Japan. As of 2019, same-sex marriage is not legal in Japan. Instead they have “partnership papers” in some cities, which gives LGBTQ couples some legal acknowledgements (but not full rights). Unfortunately this means institutions like hospitals don’t have to acknowledge these papers if they choose not to, since there is no legal obligation to do so. LGBTQ people in Japan also can’t adopt children.

Furthermore, LGBTQ people in Japan have no legal protections if they face discrimination in the workplace, when accessing housing, in educational institutions or in healthcare settings. Same-sex partners are also exempt from legal protections if they are the victim of physical, sexual or psychological abuse. As someone who lives in Canada where all of these forms of discrimination are illegal and LGBTQ rights are protected, this nationwide mindset seems very alien to me.

Another thing to note that while in North America it’s sadly not uncommon to hear about LGBTQ people being the victims of blatant acts of homophobia (verbal slurs, graffitied property, physical violence from strangers, etc), Japan is nearly the polar opposite. I feel that this is due to the differences between Japanese and Western cultures. In the west individual rights are placed above group interests, whereas Japan upholds conformity and placing the needs of the country (collectively) over individual needs and wants. It is my personal opinion that, in a nutshell, Japan doesn’t want to give LGBTQ people rights because it would require changing their legal and cultural systems; it’s easier to quietly shun LGBTQ people and pretend they don’t exist, so that the country as a whole can continue to function as it does now. Of course, the term “function” is debatable depending on who you talk to.

Another thing to note that while in North America it’s sadly not uncommon to hear about LGBTQ people being the victims of blatant acts of homophobia (verbal slurs, graffitied property, physical violence from strangers, etc), Japan is nearly the polar opposite. I feel that this is due to the differences between Japanese and Western cultures. In the west individual rights are placed above group interests, whereas Japan upholds conformity and placing the needs of the country (collectively) over individual needs and wants. It is my personal opinion that, in a nutshell, Japan doesn’t want to give LGBTQ people rights because it would require changing their legal and cultural systems; it’s easier to quietly shun LGBTQ people and pretend they don’t exist, so that the country as a whole can continue to function as it does now. Of course, the term “function” is debatable depending on who you talk to.

There is a scene in Otouto no Otto which really drives home this need Japan has for conformity. In it the older brother of one of Kana’s classmates, Kazuya, keeps sneaking by Kana’s house to try to see Mike. When he is finally able to meet Mike he comes out to Mike in a private conversation. Kazuya explains to Yaichi how he was scared to live in a world that is very heteronormative, where the norm is for boys to have crushes on girls, not other boys. Kazuya had heard slurs about gay people at school, which lead him to think that being gay was something that needed to be hidden. He had also never met another gay person so he had no one to look to for support and guidance. Even after meeting Mike, Kazuya acknowledges that he is not yet ready to come out publicly, but he is glad that he now has a supportive friend in Mike.

Author and artist of Otouto no Otto, Gengoroh Tagame, is well-known for his erotic, sadomasochistic portrayals of men in his other works. (If you go looking, know that his other works are extremely NSFW.) Rest assured that Otouto no Otto is completely family-friendly, although I will there are a few things I will note. The first is that there was one panel in the beginning where a male character is bathing and shown completely naked, with only their genital area omitted. (I have absolutely no issue with this, I’m just pointing it out since I’m rating this title as being rated for all readers and I know not everyone is comfortable with nudity.) There is also a scene later on when Mike comes home drunk and passes out with his face in Yaichi’s lap. To any adult it is instantly reminiscent of an oral sex scene, despite that not being what the scene is revealed to be about; however children are likely to miss the undertones and take the scene at face value. Lastly there are many bathing scenes throughout the series (as Japanese people bathe often) so there is lots of skin shown, but characters are always shown covered up in some manner (towel in front of the lap area, something blocking the full view of the naked body, etc) and the topic of bathing is always handled very respectfully. Nudity is never portrayed in a sexual manner. This is a title I would feel completely comfortable showing my young children.

It’s clear from the series’ cover that Gengoroh’s male characters are shown in a different style compared to male characters from most other manga series. Gone are the pointy chins and large eyes; instead we have more realistically depicted men, with Mike’s bear-like body hair even on full display in one scene. Out of the main cast, only Kana is shown to look more like “traditional” manga characters. I welcomed this change in art style and honestly I found it rather refreshing.

One of the main themes in Otouto no Otto is that of grief and the many forms it can take. The start of the manga establishes that Yaichi’s brother and Mike’s husband Ryouji is dead, so there is the standard grief for the loss of a loved one, with Mike’s grief looking a little different than Yaichi’s because Mike was naturally much closer to Ryouji and each of their relationship with Ryouji was different (husband vs brother). The reader also sees Mike have to deal with being around Yaichi and having that constant physical reminder that Ryouji is gone. Kana also experiences a little bit of grief as she grows up with a family that is different compared to her classmates’. We learn that Yaichi and his ex-wife Natsuki are divorced, and due to Natsuki’s job Kana doesn’t get to see her mother as often as her peers get to see their mothers. However the manga firmly establishes that Yaichi and Natsuki are still amicable with each other and that they do their best to co-parent so Kana doesn’t miss out on having two loving parents. There is also some minor sadness and grief shown between Yaichi and Natsuki in a couple of scenes as they explore their failed relationship and unusual family dynamic.

Otouto no Otto centers around Yaichi and his young daughter Kana, with Kana being what I would call the driving force of the story. Kids are naturally loud, curious and understanding, and much of the plot rests on Kana’s interactions with her family members and other people in her life. Kana is always asking why why why, leading the adults around her to constantly explain things to her in order to answer her questions in an age-appropriate manner. These conversations are often the source of plot progression and character development. Of all of the characters in Otouto no Otto, Kana felt the most genuine to me. Her energy, exuberance and enthusiasm for the world around her are very much that of a real child.

Otouto no Otto centers around Yaichi and his young daughter Kana, with Kana being what I would call the driving force of the story. Kids are naturally loud, curious and understanding, and much of the plot rests on Kana’s interactions with her family members and other people in her life. Kana is always asking why why why, leading the adults around her to constantly explain things to her in order to answer her questions in an age-appropriate manner. These conversations are often the source of plot progression and character development. Of all of the characters in Otouto no Otto, Kana felt the most genuine to me. Her energy, exuberance and enthusiasm for the world around her are very much that of a real child.

I think my favourite part of Otouto no Otto was watching Yaichi’s progression from someone who thought he was open-minded, who thought that being distant from his brother was a normal part of growing up, and someone who had internalized homophobic stereotypes about gay people…. to someone who came to accept his role in the dissolution of his relationship with his brother, someone who acknowledged that he had clung to incorrect perceptions about gay people, and someone who stood up for his family members when they needed defending.

One of the most simultaneously heartwarming and bittersweet scenes was near the end of the volume (I read the omnibus edition) when Yaichi finally brings himself to ask Mike to show him pictures of Ryouji. Mike shows Yaichi pictures of himself and Ryouji on his tablet and Yaichi finally, finally gets to see his brother as an actual person. Someone who grew up, met someone he fell in love with and made a life with together. Yaichi sees pictures of a trip Mike and Ryouji took together, pictures of their wedding, and pictures of Mike’s family accepting Ryouji. Yaichi sees his brother for who he really was, but also sees for the first time what he missed out on. If he had not clung to his subtle homophobia and distanced himself from his brother, he could have had this version of Ryouji in his life too. It is a very sobering moment for Yaichi, but he is able to acknowledge that in meeting Mike and allowing him to become close to himself, Kana and Natsuki, he is finally (albeit belatedly) becoming family with Mike.

Overall Otouto no Otto does an amazing job at showing its characters as complex individuals who, due to Mike’s arrival in Japan, both learn from and grow with each other throughout the span of Mike’s three week long visit. I could write more but we’re already edging into essay territory so I’ll end this review here. Just go buy this manga already! <3

Do I Recommend This Title?: Absolutely! I have nothing negative at all to say about this manga. I enjoyed it thoroughly from start to finish, and I really appreciate Gengoroh’s mastery of demonstrating how often subtle homophobia can be just as devastating (if not moreso) as calling an LGBTQ person a slur, or shunning them outright for their sexuality. His characters are realistic and relatable, and if they can grow and learn from their mistakes then we as readers can too. It’s never too late to change how we think about people or the world we live in.

Final Score: 10/10